We have heard countless times before that an underhand (fastpitch) pitching motion is far easier than a baseball overhand pitching motion, to which I couldn’t disagree more. Let’s first clarify what the typical “it’s a natural motion” is referring to. We know that overhand throwing motions, pitching and non-pitching, place a great amount of stress on the elbow and shoulder of the thrower; when the throwing arm lays back prior to release that require a great amount of external rotation mobility at the shoulder. Mobility that is uniquely acquired by the thrower through the course of their skill development as well as through the course of a season.

The pitch is delivered when the arm internally rotates, at roughly 7500 degrees per second for elite level MLB pitchers. That speed of rotation makes it very challenging for the shoulder and elbow to handle those forces being generated. It makes a lot of sense as to why we see a high number of upper body injuries in pitchers at all levels and ages.

When we look at an underhand motion we cannot compare the forces at the shoulder and elbow as that to an overhand thrower, an underhand motion does not require extreme amounts of external rotation mobility and thus does not have the speed of internal rotation causing potential damage to shoulders and elbows. This however does not by any means automatically classify an underhand pitching motion as “natural” or easier on the body.

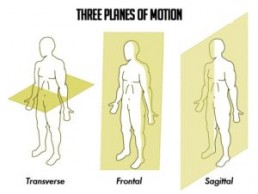

What makes underhand pitching distinctly different than overhand pitching goes beyond the direction of the arm circle. Underhand requires 2 very significant differences: 1. It goes through all 3 planes of motion (sagittal, frontal, and transverse) twice in one delivery and 2. the motion is delivered on a flat surface as opposed to a downhill slope.

What makes underhand pitching distinctly different than overhand pitching goes beyond the direction of the arm circle. Underhand requires 2 very significant differences:

1. It goes through all 3 planes of motion (sagittal, frontal, and transverse) twice in one delivery and 2. the motion is delivered on a flat surface as opposed to a downhill slope.

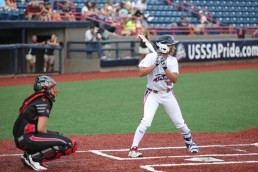

If we look at most other rotational actions in sports; hitter swinging a bat, golfer swinging a club, baseball pitcher throwing a ball what we notice they have in common is the starting position of their action is the frontal plane.

The hitter, golfer and pitcher all stand in “sideways” position, meaning the line of their shoulders and hips is parallel to the line of the intended path of the ball. Once they begin the action of the swing they move into transverse plane (rotation) to finish in a sagittal plane. The finish position has the line of the shoulders and hips perpendicular to the path of the ball.

In an underhand pitching motion, the pitcher begins their pitch from a sagittal position, shoulders and hips perpendicular to intended flight of ball, move into transvers, then to frontal, back through transverse, finishing in the same sagittal plane that a hitter or golfer finishes in.

That is a second additional sequence of 3 planes that the hitter and the golfer do not have to move through. Adding more movements through more planes of motion drastically increases the difficulty of the task because it has to be done at a high rate of speed, and it can create more chance of error in sequencing of these movements. If a pitch is delivered in a .5 of second, then we are talking about milliseconds of time when the body needs to properly move through these planes, not a great deal of time to make up for any error.

Secondly softball pitchers must do this from a flat ground position. Baseball pitchers get the advantage of the down slope of the mound helping their transition from frontal to transverse and transverse to sagittal. As the body moves with gravity down the slope it is easier for the hips to separate from the shoulders and create the necessary torque that generates the arm speed. With underhand softball pitching the flat surface works requires the pitcher work against gravity making it harder for the hips to separate from the shoulders. In both overhand and underhand pitching the throwing arm is at some point flexed overhead, this I would argue is the weakest position the athlete can be in since it requires the most amount of core strength to prevent a poor energy transfer position. Holding any object overhead is always more difficult than holding that same object with arm lying next to body. In overhand pitching when the arm goes overhead the body begins its path down the slope, while an underhand motion when the arm is overhead the body is moving forward on flat ground. Holding arm overhead, while transitioning through planes of motion, moving forward on a flat surface is a very challenging task to do without any error of movement of timing occurring. When a timing error, in either cycle of transverse plane, it places high amounts of stress on the pitcher’s spine, hips, and shoulders. Since we have two cycles of transverse plane movement, that is twice the amount of time for error to occur.

In makes sense to say that overhand motion can be more dangerous for shoulders and elbows, but that doesn’t mean underhand is free from its own challenges and dangers. Given all that I just discussed above, it makes sense that we see many pitchers with back and hip injuries, in addition to shoulder and elbow. They have to move through more planes of motion while opposing gravity more.

Given this I would argue, that underhand pitchers need to be in a consistent training program to learn, develop, and maximize the skill and speed of mastering these planes of motion. If an athlete has poor strength it is reasonable to assume they will struggle to move at a high rate of speed, and thus will miss their windows for timing of each movement plane. Skill without adequate strength is just sloppy skill teetering on the verge of potential injury.

Dana Sorensen

Co-Founder of Symbiotic Training Center

Dana is a uniquely different softball pitching instructor with combined experience as a player, coach and sports performance specialist. She began her journey as an athlete competing for Stanford University, the National Pro Fastpitch League, and Team USA. She is a 3 time All-American, 4 Time All Pac-10 team, and was recently inducted into the Stanford Athletics Hall of Fame.

The Importance Of In-Season Strength Training For Pitchers

In the softball community, there seems to be some confusion about both the value of strength training and the value of strength training in season. For me, it’s very clear: DO BOTH.

Creating a Daily Routine

Since training in season and keeping your body feeling healthy can be so difficult, it’s important to have a daily routine. Something that will keep your body moving and feeling better, but also act as a daily self assessment.

Why Practicing More isn’t the Answer

What if pitching more isn’t the answer to getting better? I know that sounds absurd, right? Everyone knows practice makes us better…. but does it?